Across the globe, law enforcement agencies are increasingly turning to advanced robotics to enhance public safety. For instance, Northrop Grumman’s Andros Mark 5A-1 is deployed to safeguard emergency responders and police from explosive threats. Similarly, the 375‑kg TEODOR robot, designed for detecting and neutralizing bombs, was actively utilized during the 2006 FIFA World Cup in Germany and is now in service in 20 NATO member countries.

Dubai is at the forefront of this technological shift. On May 24, the Dubai Police will debut its first robotic officer. Although its capabilities are modest at first, the Emirate envisions a future where robots constitute 25% of the police force by 2030. This future force could include fully autonomous androids that can pursue suspects and even make arrests.

Robotic technology in law enforcement is diverse. The Throwbot, a compact, lightweight device weighing just over a pound, can be thrown into a hazardous area to stream real-time audio and video. According to its makers at Recon Robotics, this tool helps locate armed individuals, verify hostage situations, listen to conversations, and map out interior layouts—capabilities critical during dangerous incidents.

In China, the E-Patrol Robot Sheriff is already patrolling areas such as the Zhengzhou East Railway Station. Equipped with cameras and facial recognition software, this autonomous unit not only monitors public spaces but also cross-checks faces against police databases and tracks individuals of interest until human officers arrive.

In the United States, the Los Angeles Police Department employs the TALON robot, created by QinetiQ, to assist with tasks ranging from bomb disposal to handling hazardous materials. Meanwhile, Tokyo’s Metropolitan Police unveiled a drone in 2015 designed to intercept and capture other drones—a response that followed a quadcopter carrying radioactive materials flying onto Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s office rooftop.

Even in less high-tech regions, innovation is taking root. In 2014, Kinshasa in the Democratic Republic of Congo introduced two basic androids at a busy intersection to monitor traffic and relay video back to the police for analysis. For specialized tactical support, the SWAT teams in the United States have turned to devices like the SwatBot, developed by Howe and Howe Technologies in collaboration with the Massachusetts State Police. This multi-functional robot serves as a ballistic shield, door breacher, and debris remover in dangerous scenarios. Similarly, the PackBot, renowned for its maneuverability over stairs and rough terrain, assists with bomb disposal while transmitting real-time sensor data.

Another notable tool comes from MESA Robotics, whose device aids in surveillance and the safe handling of hazardous materials. The LAPD’s Batcat, a remote-controlled vehicle weighing nearly 39,000 pounds and outfitted with a telescopic arm, has been used to safely transport large vehicle bombs, thereby minimizing risk to human life.

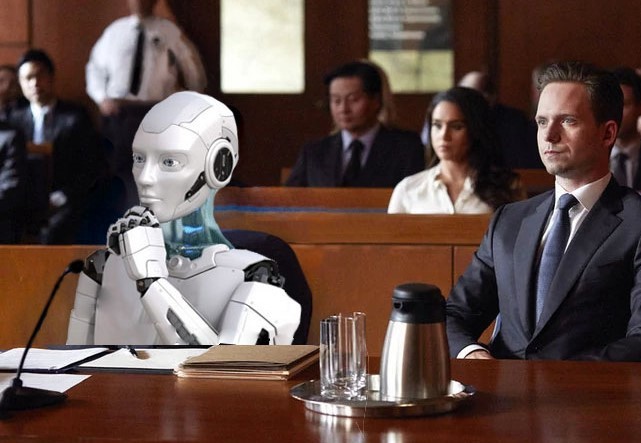

The integration of robotics into policing has sparked debates that touch on ethics, legality, and public safety. Drawing inspiration from Isaac Asimov’s famed Three Laws of Robotics—which emphasize non-harm, obedience to humans, and self-preservation—experts are now questioning how these principles might apply when a robot’s actions result in arrests or other legal consequences. Could a machine’s conduct ever be considered just or safe in the complex realm of criminal law?

Dubai’s initial foray into robotic policing comes with its own set of challenges and ethical dilemmas. The first unit, an adapted humanoid robot called REEM designed by PAL Robotics in Spain, will be stationed at key public venues such as tourist spots and shopping malls. This 220‑lb, 5‑foot‑6‑inch machine, capable of speaking nine languages and interacting with citizens, primarily serves as an information kiosk by providing access to police services, paying fines, and more. Although its facial recognition technology currently operates at around 80% accuracy, live video feeds are sent to command centers to bolster its effectiveness.

Looking ahead, Dubai Police aims to develop a fully operational robotic officer that could perform duties similar to those of human officers. However, significant technical hurdles remain—such as achieving human-like dexterity and decision-making under dynamic conditions. Experts like Alan Winfield, Professor of Robot Ethics, caution that equipping robots with firearms would be a “red line,” given the enormous risk of unintended harm. Likewise, concerns about algorithmic bias and accountability loom large, as errors in robotic behavior raise questions about liability among manufacturers, programmers, and operators.

Despite these challenges, proponents believe that integrating robots into police work could enhance efficiency, reduce risks to human officers, and ultimately transform how public safety is managed. While some fear that this technology might erode the personal touch of community policing, others foresee a future where humans and robots work in tandem to serve the public more effectively.

As this technological revolution unfolds, cities like Dubai are poised to be key testing grounds. The reception of these early robotic models will likely shape public opinion and policy in the years to come, balancing the promise of increased safety with the perils inherent in delegating critical decisions to machines.